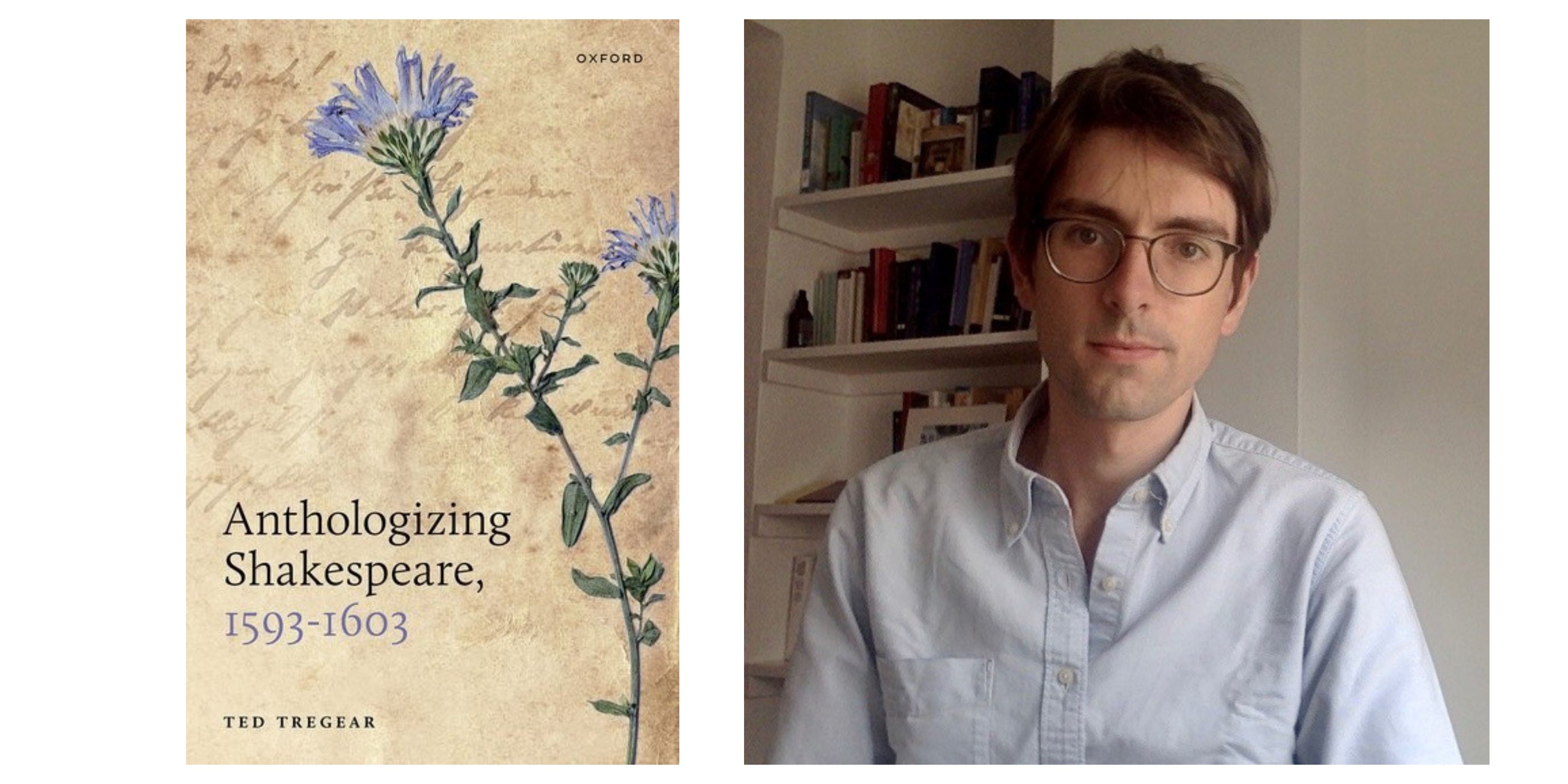

A new book by Gonville & Caius College Fellow Ted Tregear explores how William Shakespeare appealed to the reading habits of his contemporaries – including those who compiled anthologies from extracts of his writing.

Anthologizing Shakespeare 1593-1603 takes its lead from a group of five anthologies published between 1599 and 1601, halfway through Shakespeare’s career, which featured excerpts from his poems and plays. Expanding on his PhD, Ted asks whether Shakespeare anticipated being read like this, in extracted and anthologized passages—and whether that changes how we read his works.

“I was asking, how do these anthologies help us read the plays differently?” Ted says.

“How do they guide us towards the most anthologizable passages, passages which Shakespeare might have put there to be anthologized?

“They are moments where Shakespeare is inviting readers to take extracts from his works, but asking them to reflect on what they’re doing. And by doing this, he’s leading them into the central questions of his poems and plays.”

Ted describes the book as “really an excuse to get closer to the texts themselves”. Anthologizing Shakespeare offers detailed readings of poems and plays from Shakespeare’s first decade in print. One of those plays is Hamlet, a tragedy written at around the time Shakespeare was being most heavily anthologized.

“In some ways, Hamlet very obviously shows the traces of those anthologies,” Ted adds. “It’s a play that is obsessed with quoting and commonplacing and anthologizing, and abounds in precepts and maxims and sententiae that you can take out of context and re-use in other situations.

“When Hamlet was first printed in 1603, it was printed with quotation-marks in the margins next to certain speeches. Those are telling early readers: ‘these are the lines you take from this’, ‘get your pen out and write these down in your commonplace book’. From the beginning, when readers encountered Hamlet, they encountered a play that was offering them up material for commonplacing.

“The difficulty is a lot of those commonplaces are spoken by characters we think of as, at best, tangential to the action—and at worst, as idiots. Characters like Polonius. Polonius always loves dispensing these maxims of advice. So we’ve got this contradiction: how is it that a play is packaging, as authoritative words of wisdom, lines that any good reader should approach with caution?

“That contradiction is what drew me to write about the play. But the more I worked on it, the more I discovered this whole rich domain of tragic poetics and tragic theory behind these sententiae.

“From Aristotle onwards, good tragedies are thought to contain a certain element of thought: what Aristotle calls dianoia, and what his Latin translators call sententia. So in including sententiae like this Shakespeare isn’t just drawing on the contemporary energies of the anthologies themselves, he’s tapping into a longer tradition about the relationship between thought and drama.”

The analysis led Ted to consider a question at the heart of Hamlet – how thinking can be put onstage. He compares the different ways its characters think: whether that’s Polonius, who offers easily extractable sententiae, or Hamlet, who obsessively gestures towards “that within”, but can’t seem to say what he means.

Rather than be daunted by finding a new strand of researching Shakespeare, Ted was encouraged by the opportunity.

Ted, who is now researching the relationship between philosophy and literature in the seventeenth-century metaphysical poets, adds: “Although you can sometimes feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of what’s there, there’s also a freedom in that.

“A lot of what I was doing was bringing together areas of research that hadn’t really been talking to one another. It’s in a sense an invitation to be creative and pick your own way through a crowded field.”