Print and the material book

7 June 2022 (online)

The press of the Paris printer Josse Badius, called Ascensianus (from Thomas Netter's Doctrinale Fidei Catholicae, 1532, M.8.4).

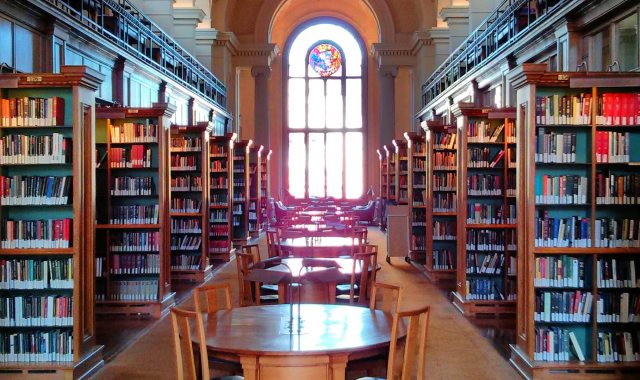

The introduction of printing in Europe from 1450, employing Johannes Gutenberg's innovations of movable type and the screw-and-lever press, rapidly altered the form and functions established for the manuscript (handwritten) book. Whereas the manuscript process produced single copies, often at the personal instance of a customer, printing enabled and – given its much higher capital requirements – demanded mass production. As such, printers had to offer their books to a speculative market of unknown customers.

This exhibition explores how the new technology created pressures that permanently transformed the material book. Printers turned from parchment (prepared skin) to paper, which dried faster and so ensured a shorter turnaround to market. Title pages became necessary to identify books among copious shop stocks. The logic of the printing process led type design away from the model of script, while space took over the role of colour in organizing text, and rich hand illumination gave way to a reproducible graphic form in the woodcut.

Page numbering became standard and indexes became common, as did lists of errors (errata), which the intensified division of labour in the printing house multiplied the occasions to introduce. And the licences or imprimantur ('Let it be printed') that began to preface books bore witness to a turn from reaction to prevention in censorship, as print's potential to spread heresy as well as orthodoxy, dissent as well as authority, became an urgent concern for churches and states.