The Gallipoli Campaign

The allies landed at Gallipoli in April 1915 and, in the words of the Imperial War Museum:

"of all the varied parts of the world where British and Commonwealth forces were deployed during the First World War, Gallipoli was remembered by its veterans as one of the worst places to serve."

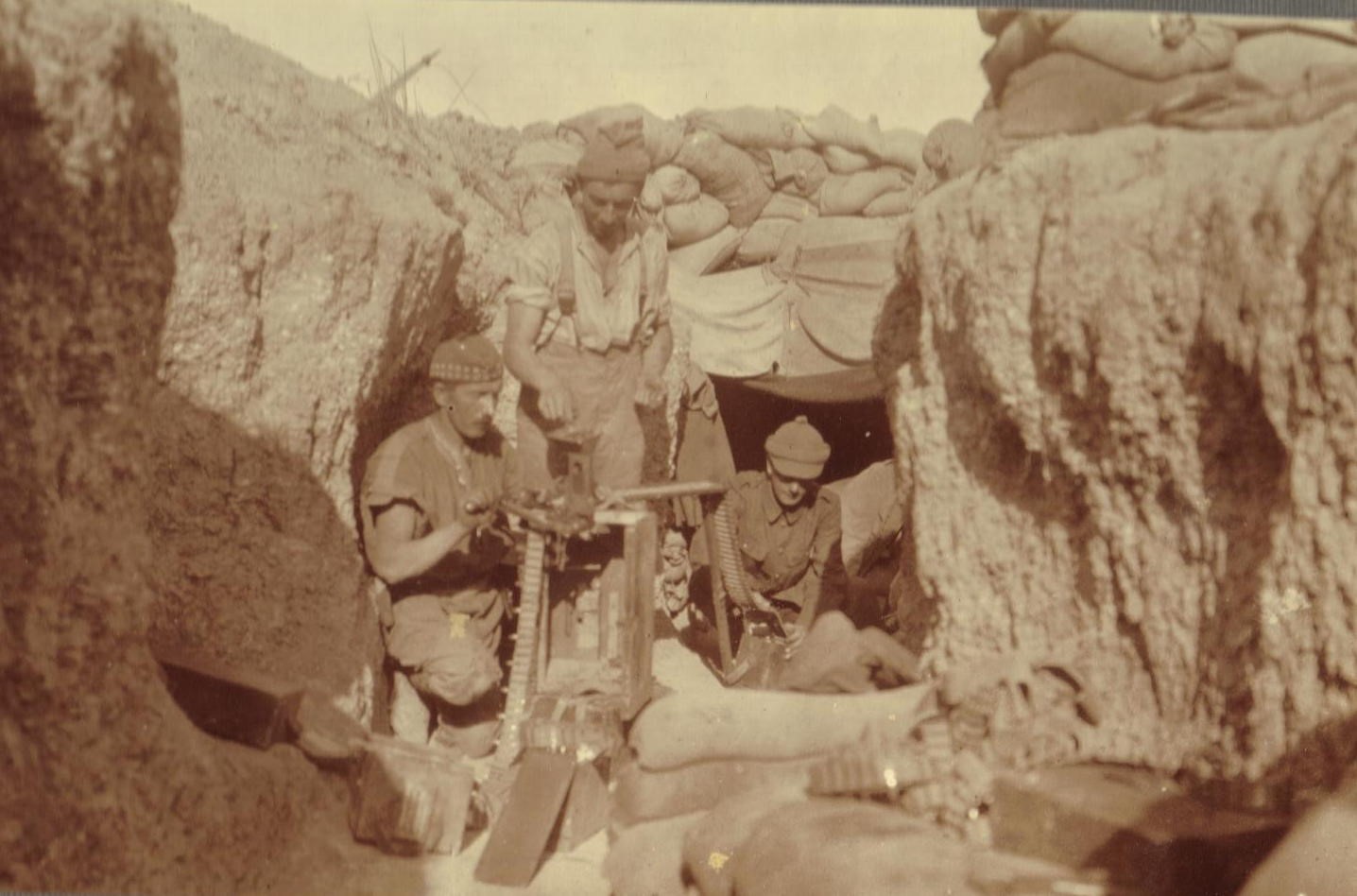

The fighting there during the nine months of the campaign was some of the fiercest and carried out under extremely difficult conditions. One third of the casualties there were due to disease rather than battle. Many problems were due to the difficult terrain, intense heat, lack of water and supplies and the superabundance of flies and lice. The flies were, in part, because of the impossibility of collecting the dead from no man’s land and from the very primitive sanitation. Unsurprisingly, there were serious outbreaks of dysentery and enteric fever.

August 1915 saw one of the most disastrous actions of the war when Britain attempted to relieve the stalemate at Gallipoli by landing at Suvla Bay. Caius lost seven men in that action and they had been at the front between 1 day and 3 weeks. In 1931, Col. Crookenden wrote to Brig Gen. Aspinell-Oglander about this engagement and his letter survives in the war diary:

"I think the English language is hardly adequate to describe the state of affairs which existed at Suvla on 9th August 1915, when the 15[9]th Brigade landed there.

Your picture is good as far as it goes, but still does not convey the atmosphere of indifference, laissez-faire and chaos into which we plunged. While the battalions were trickling along the coast road at the foot of Lala Baba, and my clerk was handing out maps from a packing case to officers as they passed I went up to the top of the knoll. I saw the Salt Lake (dry) covered with men advancing towards me (fugitives). I saw the HQ Staff (Lindley and Hammersley) of two divisions in a trench on a forward crest – of course in full view of the enemy – this was only on a par with everything else. After examining the situation carefully I offered to capture the distant objective, provided I was given an hour with the Company commanders and their maps and compasses on top of this Lala Baba knoll.

I was threatened with arrest and told to send two battalions to “report themselves to Br -General Sitwell”. “Where?” “In the bush”. “What does Br -General Sitwell look like?” “I don’t know”. This is not an extract from a comic opera, but a verbatim report of two trained Staff College graduates giving and receiving orders on the battlefield. On my refusing to convey any such silly order, I was again threatened with arrest and the order was given to my Brigadier-General. The 4/Cheshires and 5/Welsh went off and we never saw them again until daylight on the 10th. …

… the left hand man found a Brig – Gen and his staff lying on their backs resting in the shade of a rough hedge. This was Br – Gen Sitwell. He refused to give any orders, or information, and reiterated ad nauseam “This is your show”. I nearly brained him."

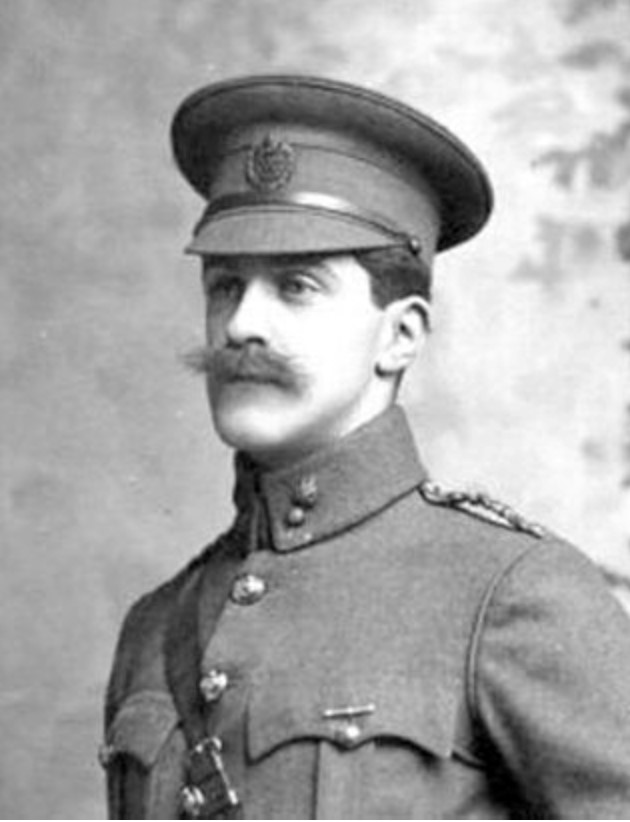

A contingent  of the Territorial unit, the Kent Fortress Engineers sailed for the Middle East from Devonport on the 11th October, one day after the decision had been taken to stop all such shipments of soldiers. They were skilled bridge builders. On board was Captain David Reginald Herman Philip Goldsmid-Stern-Salomons, known to his friends as Reggie. He, together with his father, had been very influential in recruiting the 231 men in this detachment who mostly came from Southborough, a village near Tunbridge Wells.

of the Territorial unit, the Kent Fortress Engineers sailed for the Middle East from Devonport on the 11th October, one day after the decision had been taken to stop all such shipments of soldiers. They were skilled bridge builders. On board was Captain David Reginald Herman Philip Goldsmid-Stern-Salomons, known to his friends as Reggie. He, together with his father, had been very influential in recruiting the 231 men in this detachment who mostly came from Southborough, a village near Tunbridge Wells.

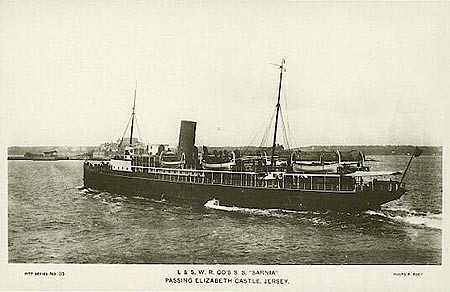

The outwar d journey was uneventful but the weather took a turn for the worse on the 28th October 1915 as they sailed out of Mudros for Gallipoli on HMS Hythe. It was very rough and many were seasick. It was a cruel coincidence that the Hythe was a cross-channel cargo steamer requisitioned from South East and Chatham Railways and Reggie’s father was a director of this company. At about 8pm just before reaching their destination, HMS Sarnia loomed out of the darkness and hit the Hythe at speed causing a huge hole in her side; Hythe sank within ten minutes. Most of the soldiers were on deck but hampered from escape by newly fitted awnings. Reggie stayed on board the overcrowded and ill-equipped ship to help the men as best he could and was one of about 130 from the unit who drowned.

d journey was uneventful but the weather took a turn for the worse on the 28th October 1915 as they sailed out of Mudros for Gallipoli on HMS Hythe. It was very rough and many were seasick. It was a cruel coincidence that the Hythe was a cross-channel cargo steamer requisitioned from South East and Chatham Railways and Reggie’s father was a director of this company. At about 8pm just before reaching their destination, HMS Sarnia loomed out of the darkness and hit the Hythe at speed causing a huge hole in her side; Hythe sank within ten minutes. Most of the soldiers were on deck but hampered from escape by newly fitted awnings. Reggie stayed on board the overcrowded and ill-equipped ship to help the men as best he could and was one of about 130 from the unit who drowned.

Reggie had four sisters but was the only son of his father. His father, Sir David Lionel Salomons, was also a Caian, an engineer, a great reformer, philanthropist and benefactor of the College.

December 1915 saw the beginning of the removal of allied troops from Gallipoli but this was not a quiet time. Winston Churchill had been an architect of the whole Gallipoli campaign but he had resigned from the government in November 1915 in order to join the fighting in France. Lord Kitchener had refused to accept the advice that there should be a withdrawal but, after visiting the peninsula early in November, he advised that the 93,000 troops should be removed.

That November, the weather turned very stormy and cold at Gallipoli. As a result 280 men died and about 15,000 suffered various degrees of frostbite and exposure. The landing piers at Anzac and at Helles had been severely damaged in a storm two weeks earlier so it was mid December before the evacuation began to get underway.

The 1st Battalion, the King’s O wn Scottish Borderers had been in Gallipoli since April that year and had been at several of the bloodier engagements, losing about one third of their strength at Y beach alone. December was not a quiet month for them either as they were under constant bombardment from the Turkish lines that resulted in many more casualties. Their evacuation was not completed until early in the New Year when the Battalion were sent to Egypt.

wn Scottish Borderers had been in Gallipoli since April that year and had been at several of the bloodier engagements, losing about one third of their strength at Y beach alone. December was not a quiet month for them either as they were under constant bombardment from the Turkish lines that resulted in many more casualties. Their evacuation was not completed until early in the New Year when the Battalion were sent to Egypt.

One of those to die in December with the 1st Battalion was Henry Gordon. He was a Scotsman from Maxwelltown and had been educated in Ardvreck School and Bradfield College. He had been due to matriculate at Caius in 1914 but, like so many men at that time, he went straight into the army, serving first in France where he was wounded (near Ypres), shot in the thigh by a rifle bullet. He sailed for Gallipoli in April 1915 so saw all the fierce fighting that characterised that campaign before he died of wounds on the 19th December 1915 in No: 17 Stationary Hospital, Dardanelles which was near V beach. He was 19 years old.